So, let’s talk about weebhax. The rather unexpected juggernaut of 5.5.2 dealt a harsh blow from Nintendo, patching out browserhax and leaving many users without an entrypoint. The hunt was on! We’ll pick up the story at the genesis of what I’m working on: the discovery that, inside the Crunchyroll application, several files are downloaded over an insecure connection which we can intercept and replace with our own, arbitrary content.

Woo-hoo, right? This is where I got excited and started posting things on Twitter.

I messed around for a little while and found out that pretty much all of the libraries used to do things like rendering webpages and playing videos haven’t been updated in quite a while. As an example, the WebKit used has been dated around 2011 (yes, that’s 6 years old!) which means it’s missing a lot of security patches. The vulnerability I happened upon and have been working on is the same one used to exploit the Internet Browser on 5.5.1, a buffer overflow in the mp4 decoder. So, I hear you ask, why isn’t there a Crunchyroll exploit already out there? Surely you can reuse the code from 5.5.1?

To explain what’s going on here, we first have to delve a little into how this exploit works in a perfect world before we can get into why Crunchyroll is far from perfect.

The vulnerability is what’s called a buffer overflow. Think of the Wii U’s memory as a long, thin piece of paper - the program writes stuff on it in pencil and can read that data back as it needs it. When it doesn’t need the data anymore, it rubs out the pencil and writes something else. To help manage the paper and decide if data is still needed, management systems are in place to allocate, or set aside, parts of the paper for a specific purpose. If the program wants to write something down, it will first go to the allocator and ask it to reserve a spot for the data. The program can then write away without having to worry about another part of the program erasing it and writing something else. As long as all parts of the program go through the management system, the data is safe.

So, what happens during a buffer overflow? In short, these vulnerabilities occur when the program doesn’t check if the data it wants to write fits in the section of paper it allocated. If you can trick the program into allocating a piece of paper that is too small for the data it’s writing, it will just keep on writing outside of where it’s supposed to. In the right conditions, this could be a Big Problem. Let’s have a look at how this works in an example.

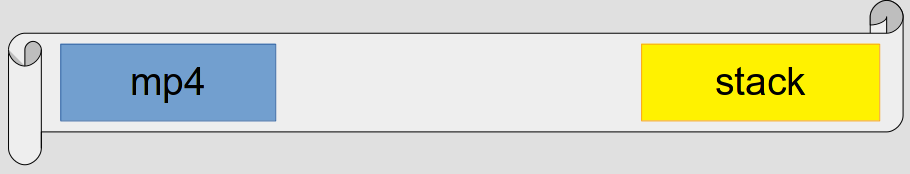

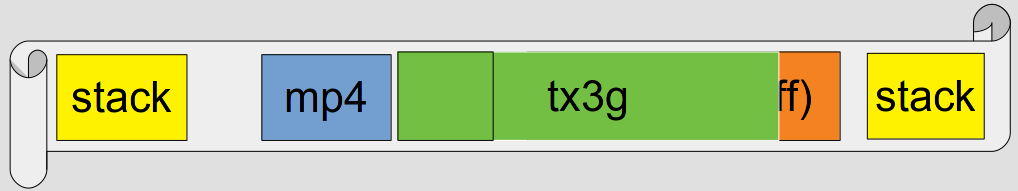

So, here’s our piece of paper. The program has already downloaded our mp4 file and written it onto the paper, and is ready to decode it - though it hasn’t started yet. Our paper looks something like this:

You can see the mp4 file on the left, some unimportant space in the middle, and on the right is what’s called the stack. The vast majority of programs are built using sections of code called subroutines - the idea is that you have a subroutine that performs a specific task (doing some math, allocating memory, drawing the screen) that you jump to as neccesary. One caveat of this programming model is that your program needs to know where to go back to after a subroutine has completed its task. This is solved using a stack - a special section of memory where the program stores addresses that tell a subroutine where to go when it’s finished.

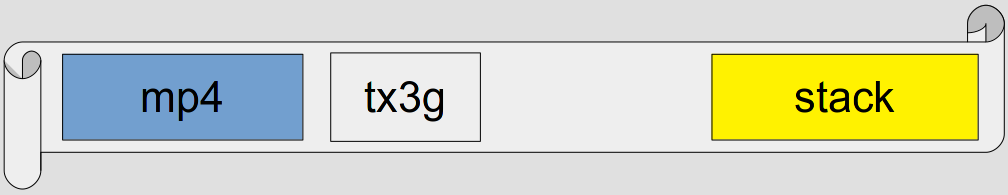

Anyway! Now that the program is ready to start decoding our mp4, the stage is set for our exploit. Our mp4 has a ‘tx3g’ section, which causes the decoder to do two things:

- Allocate a section of memory with the same size as the section size listed in the mp4

- Copy data from the mp4 file into this new section of memory

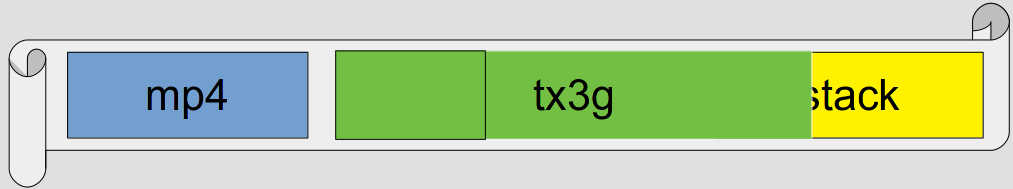

So, what’s the problem here? Well, when figuring out how much memory to allocate, the decoder adds the size from the mp4 with another number from the mp4. By carefully controlling these two numbers, we can abuse the fact that computers have an upper limit on the size of their numbers to perform what’s called an integer overflow - to cut a long story short, the decoder ends up with a number that’s smaller than the ones it started with. The decoder will now allocate a buffer that’s too small for the data it intends to write. We got it!

Here’s that in pictures. The program allocates a section of memory in response to the tx3g section in the mp4…

Our integer overflow tricks from before mean that the program starts to write too much data, sailing beyond the end of the allocated section…

Ta-da! The program has unknowingly overwritten the stack with data from our mp4 file. If we craft this data correctly, we can make subroutines in the process of returning jump wherever we’d like instead of where they’re supposed to! From there it’s a case of ROP, JIT and finally code exec (subjects for another day).

This, of course, is an ideal case. It’s more or less what happened in the browser (as far as I know, the tx3g buffer actually ended up inside the stack) and is an example of how it works when everything goes to plan.

Crunchyroll is an example of when everything does not go to plan.

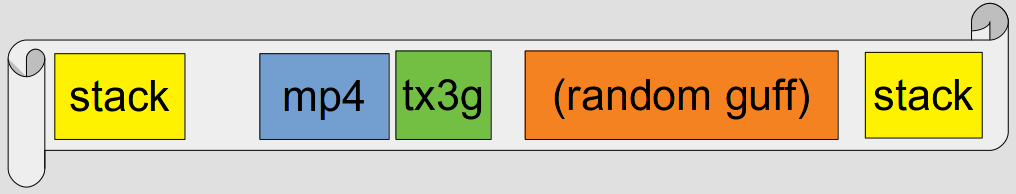

In the process of trying to apply this technique to Crunchyroll’s video player, I’ve learned of several key differences between it and the Internet Browser. For example, when Crunchyroll loads up our video (just before the buffer overflows) the memory looks like this:

Since the decoder copies data from inside our mp4, it grows along with the amount of memory we want to overwrite. This quickly reveals another problem: there’s an upper limit on how much memory we can overwrite. The app will just give up if an mp4 is too big. If we overwrite as much as we can, we’ll end up with something like this:

So close! We can’t quite get to the stack with this overflow, which means we can’t get easy code execution. Instead, we have to rely on the random guff… Not ideal. Sure, there’s still code addresses in there which we can overwrite, but it’s not nearly as reliable as the stack. There’s also the small matter of finding the stuff to overwrite in the first place, along with picking one that will be used before some other side effect of the overflow crashes everything, and dealing with the constantly-changing nature of the memory layout… It’s a lot to overcome, and we haven’t even talked about JIT yet.

Hopefully this post gave you a bit of insight into how these exploits work, and the problems one faces when trying to exploit them under weird and wonderful applications. Just because there’s a vulnerability, bug or crash, doesn’t mean it’s easy to exploit or even can be. I intend to keep working on Crunchyroll at least until 5.5.2 is hacked one way or another, though it may not be this specific vulnerability. Only time will tell.